Depicted on the stage was a mansion like those

to be found in Palm Beach. In this case, though, the mansion was under

great disrepair and even corruption. Vines had long ago penetrated from

the garden, grown into the space, and then died. There was a grand

curved staircase and a marble floor, cracked and warn.

There was also a chandelier as well as a newel

post light at the foot of the stairs. These too were in disrepair.

Closer inspection revealed wires strung to these fixtures from a

bicycle-like contraption up-stage. Could this be a Gilligan’s

Island style pedal generator?

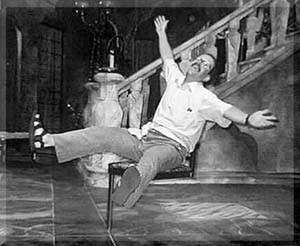

The only furniture in view was a single chair

and a chaise (see the production photos). Also in the stage picture was

a suit of armor, standing by the archway under the steps.

The house curtain was used in this production,

as it was very important for some stylistic choices we made in

production (see below). The entire picture was further framed in by a

bronze-like Art Deco portal.

The set proper consisted of a series of walls,

french windows, archways, a colonnade, beams overhead, and cobwebs.

Decorating the walls were a series of animal heads, decayed by years of

neglect.

Discussion of concept began with a brash quip

from the director, John Dennis:

"In this production we show

that....Norma Desmond has a neighbor..."

His tone of voice was quite sarcastic and we

all understood immediately his point. There are those who are born of

society, and those who aspire to it without a clue as to what life at

any level is about. In Moliere’s text, social conventions are turned

on their head. In this edition this is quite magnified.

John Dennis had suggested the Hollywood of

Sunset Boulevard as our backdrop. He wanted to find a parallel in a

society where pretense became everything, where even homes themselves

were some sort of theatre set, a facade of life rather than anything

real or anything to be taken seriously. The Director also came to the

discussions with a

plan to make liberal reference in the

characterizations to various comedia Hollywood actor types. We had a

Tarzan entrance, swinging across the stage from the top of the stairs on

a vine. One of the characters too was patterned after Chico Marx.

The spirit of Jack Benny was also important for

the director. Mr. Dennis particularly noted his lovability intertwined

with his absolute miserly qualities (in character at least). Benny’s

character would go to infinite, almost improbable lengths to save even a

penny. Dennis proposed that we even duplicate Benny’s basement vault

guarded by alligators (we did).

One thing I greatly admired about working with

John Dennis was the way, as a director, he would set a course, but then

allow his collaborators to run with it. For instance, the director

thought it would be a nice idea for things to be in such decay that when

a piece of the set would break off, Harpagon would simply affix a price

tag to it for some future sale.

Often my role in the directorial proposals was

to take the basic ideas and then to test the limits of how far we could

go. The director’s idea of affixing price tags made me think of the

scenic circumstances set out in Moliere’s text. Moliere calls for

furniture and boxes to be assembled in the grand hall for some sale. Our

Harpagon though, with a character taken to extreme, would have sold all

his furniture long ago. This is what reduces him to selling pieces of

the set, broken chair legs, etc. What is especially fun is that Harpagon

is so driven by his miserliness that he doesn’t even act as though his

decor is unusual.

I proposed going even farther yet, and this

allowed for a nice fusion between all of the design elements. The idea

for the generator, for instance, I believe was mine. If he is so int

saving every penny, our Harpagon would certainly not be above

"theft of services". The device of a pedaled generator made

for some very funny blocking, pacing, and lighting opportunities. The

director chose certain key moments in the show. At these points, the

lights would suffer a "brown out" until the servant, or in a

pinch Harpagon himself would pedal his way into the light.

The first time this device was used was

especially interesting. At first the audience thought it was a lighting

mistake. Revelation that the strange contraption upstage was a

generator, thus became that much more fun.

If Harpagon was such a complete miser in our

version, why then would he have multiple servants as Moliere had

written. In a stroke of collaborative inspiration we all agreed to a

scheme whereby one actor would play all of the servant roles, especially

that of the chauffeur and the cook. The director and costume designer

then set out to find the perfect Hollywood archetype for these two

characters. They chose to portray a German chauffeur (with a Duesenberg

of course) and a French Chief. The actor playing the dual roles was then

required to shave his head. This allowed for a most remarkable lazy-susan

type hat device. Half the hat was that of a chauffer, the other being

that of a chef. This mode of presentation became very funny and was

especially entertaining during scenes requiring arguments between the

chef and the chauffeur!

More evidence of the collaborative process

allowing us to test the extremes came with the director asking if the

chair could have a leg break off (Harpagon would put a sales sticker on

this too). The director thought it would be both fun and revealing when

Harpagon would then sit on the three legged chair.

Here too, I used the director’s idea to

postulate the end projection of the theory: What if more than one leg

could break off? What if three legs broke off, and what if Harpagon

could sit just as soundly on a one legged chair as an ordinary mortal

could on a 4-legged chair? Our Harpagon weiged over 200 pounds so it

took some special steel alloy and welding to realize the trick but the

effect was quite rewarding. In the last production photo presented here,

you can faintly see the chair in its one legged configuration, down

stage left.

While we pushed the limits through our visual

commentary, the director was careful to pace the gimmics and to ration

them well. In this way, each time, these came as an absolute surprise to

the audience, thinking they had already seen the limits of this

character’s potential for buffoonery.

After the director gave us our "Norma

Desmond" marching orders, I looked hard for visual research related

to Palm Springs. While I found some photos of the homes of stars, the

few I found were mostly bad modern restorations. I came across, though,

a vary high-end Abrams publisher book dealing with the architecture of

Palm Beach. I always confused these two "Palm" cities in my

mind and was further confused when I first looked at the book. The

architecture between the two cities looked similar to me. As it turns

out this was one of those very happy accidents in the work of a

designer.

Palm Beach in Florida, at least as we think of

it, was founded architecturally, by Hollywood’s mega-stars trying to

escape from the now crowded Palm Springs in California. More

interesting, especially to our production and to theatre in general, the

prime architect of the look of the homes in both locations was from

Joseph Urban. While I was very familiar with the pioneering stage design

work of Mr. Urban, I had been unaware that he was also an architect. The

stars would see his work on the stage and would then commission him to

design their homes. It is thus no accident that the homes read almost

more as sets in some fantasy life than as home as us non-stars would

know them. The whole concept of pretense in the way we live as well as

delusion and self-delusion was thus ensconced within this mode of

architecture itself.

I have of course seen thousands of shows in my

lifetime and have worked directly on hundreds. Yet I cannot think of any

that had a more fun or striking opening moment than that of this

production, as orchestrated by John Dennis, the director. Within the

first few moments he jerked the audience, almost physically from their

seats, as though they were in some Disney flight simulator ride - All

the more surprising in a staid classical comedy such as this one. Again,

this moment demonstrates a synergy between directorial vision, physical

action, and other design elements, particularly in the arena of scenery,

props, effects, and sound.

When the audience entered the theatre, they saw

a very traditional intimate proscenium theatre with warm tones. There

was a maroon velour curtain lit with traditional red curtain warmers.

The curtain was framed by the bronze portal. Preshow sound was

overly-traditional music one would expect of a generic Moliere show. I

could imagine that many audience members by this time would have been

thinking: "finally CSF is doing a classic TRADITIONALLY!"

As in such "traditional" fare the

house lights dim, the curtain goes dark, the sound fades, as the

audience hunkers down for yet another classical performance. Instantly

though, the audience, with the opening of the curtain, is jarred into an

environment totally at odds with expectation. Smoke billows from the

stage into the audience. The stage itself is bathed in eerie stormy

light. It’s as though we are in some sort of Gothic melodrama, in the

bogs around Scotland. The music in an instant transition with the

curtain is loud, brash, stormy, and indeed is interspersed with the

sounds of a storm. "Wait, are we in the right theatre? Is this

Moliere, or Dracula....and what would Dracula have to do with Moliere?"

the audience must at an instant wonder.

Then, from within the fog, at the top of the

steps, enters a shadowy character clutching a box as though his life

depended on it. He is clearly agitated, perhaps even paranoid as he

moves down the rocks - or are they stairs - hard to tell in the fog. He

makes his way down stage. From out of the fog he lifts a trap door and

the audience is treated to a snapping alligator right in their faces.

The figure descends from view, the trap door

slams loudly, and then....at an instant, a count of zero, the world

reverts back to the world of Moliere. The fog is gone, the lights are

bright, the music is a twinkling ditty, as the young lovers enter

wearing summer clothes of pastel colors, while they hold their tennis

rackets. Clearly, this is to be an evening FULL of surprises. It was,

and it was a joy to work on.